Challenging the ‘selective forgettings’ of the family archive.

I am going to reflect on my personal project, Reaching Back, through the lens of some reading I have been doing on the concept of ‘the archive’.

This was the culmination of months of research into my own family history but built on years of wanting to know more about the Leeming (and Ellis - my grandmother’s maiden name) families from Calcutta – the place my father was born in 1931 and somewhere his ancestors had been for generations. There were well-worn stories associated with their lives there, but the narrative was also rife with silences.

Michel Foucault writes that the archive is not so much a physical entity as the system we inhabit – namely the language which dictates what can be talked about and what should be forgotten. This feels fitting – the romanticised stories of life in India were celebrated, while the more difficult conversations about racial politics and awkward ‘in-between’ social status for Anglo Indians were avoided at all costs.

Situating myself

My pushing back against this ‘policing’ of the narrative involved collecting snippets of oral history from different relatives and weaving them together with titbits gleaned from other sources to create something new. This included reading about the Anglo Indian community, the Raj, the British Empire and the East India Company.

It also involved using the genealogy websites Find My Past and Ancestry to do the tedious work of searching for documents – the British were keen record-keepers across their empire and much of this is now becoming available online. Baptism records, marriage registers and burial registers were key, along with records for military orphanages, army regiments and wills. However, access to these collections costs hundreds of pounds in annual fees, so while digital archives are revolutionary, there are limits to accessibility – in this case gatekeeping in service of commercial interests.

Some documents could not be located, resulting in gaps in knowledge but it was impressive what I could find – the earliest item being something on the British Library website dating back to 1690, which names a direct ancestor who journeyed from France, to Britain and then to the British-ruled island of St Helena. His descendent then made it to India more than 100 years later, where he served as a solider. There is likely to be lots more in official archives in London and India - a retirement project perhaps.

In his book Archive Fever, Derrida links the archive with memory, forgetting, and the Freudian concept of the human ‘death drive’ (self-destructiveness). This argues that because memory is unstable, archives are created to reinforce narratives for the future - but these are also unreliable and incomplete. The boundary of Derrida’s archive is guarded by the arkons, the holders of power; in this case the meticulous Raj authorities who shipped these documents back to London, where they were carefully filed away for posterity. However, it became very clear for me during my own excavations within the archive/s that something important was definitely missing.

The women - who represent connection with India - are almost entirely absent from these narratives.

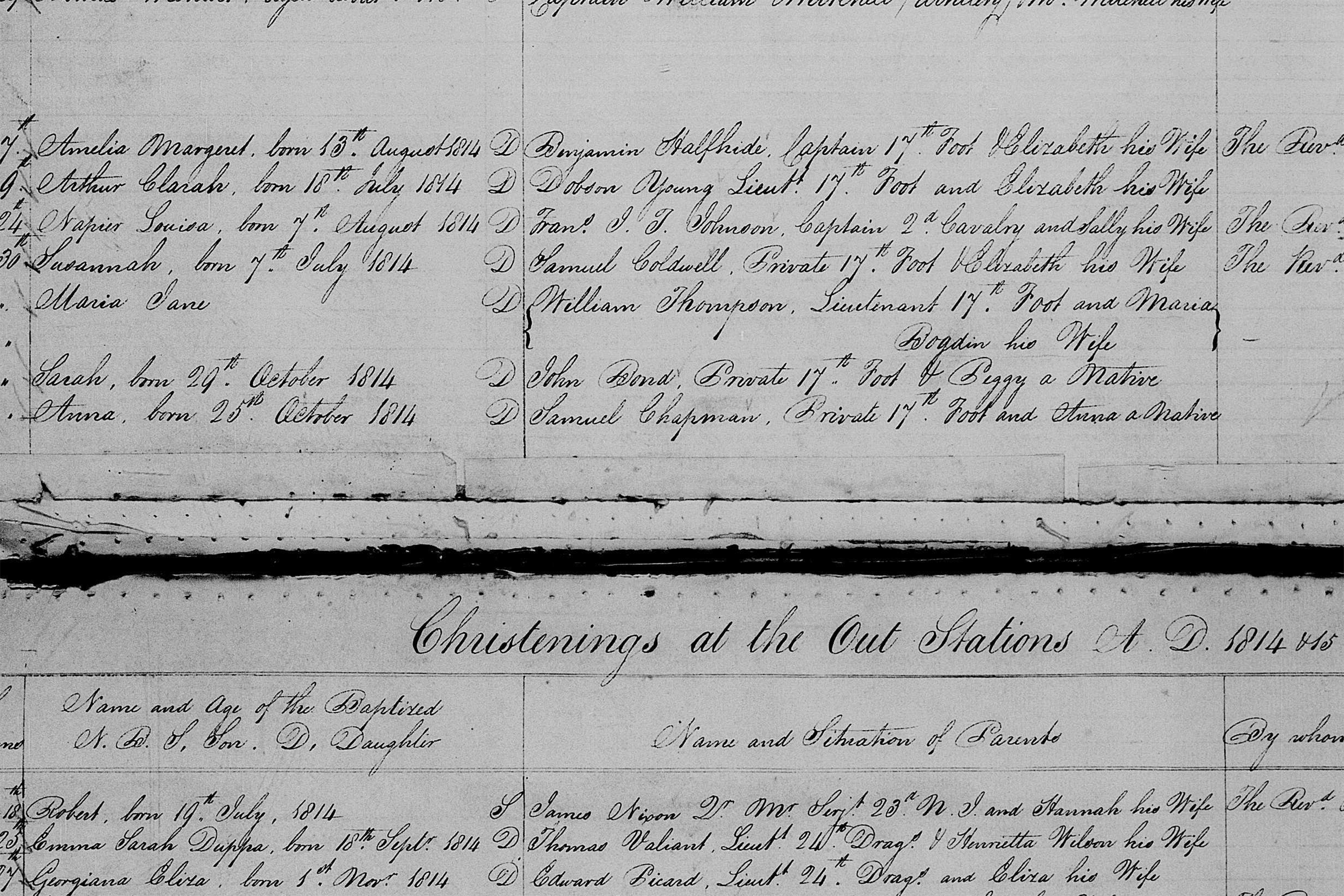

The origins of the Anglo Indian community are tied up with the early years of European colonisation in India, in the 17th and 18th centuries. Then, few European women made the long journey to the subcontinent, so East India Company men frequently formed relationships with Indian - and subsequently - mixed race women. However, these women are hard to locate within the records, most of which are church-related. If relationships were formalised through marriage, these women would have first been baptised - a process which leads to them being given a new (European) name. If they were unmarried they were missed off the baptism record for their children – as I looked more I realised that these absences are a clue. Very occasionally you see a designation such as “Anna, a native” (something I found in one case from the early 1800s) but this kind of overt ethnic categorisation is rare - more commonly their true identity fades away into invisibility, an example of what Stoler calls the “selective forgettings” performed by archives. This is another example of how power is expressed – in this case within a colonial archive – and whose traces are allowed to shine through. The only link we have to these women is through DNA tests which clearly show they existed, irrespective of whether the archive or previous family narratives want to admit it.

Samuel Chapman is one of my ggg grandfathers, a European solider employed by the East India Company. ‘Anna’ is one of a number of Indian women who must exist within our family tree but she’s the only one who is not a gap.

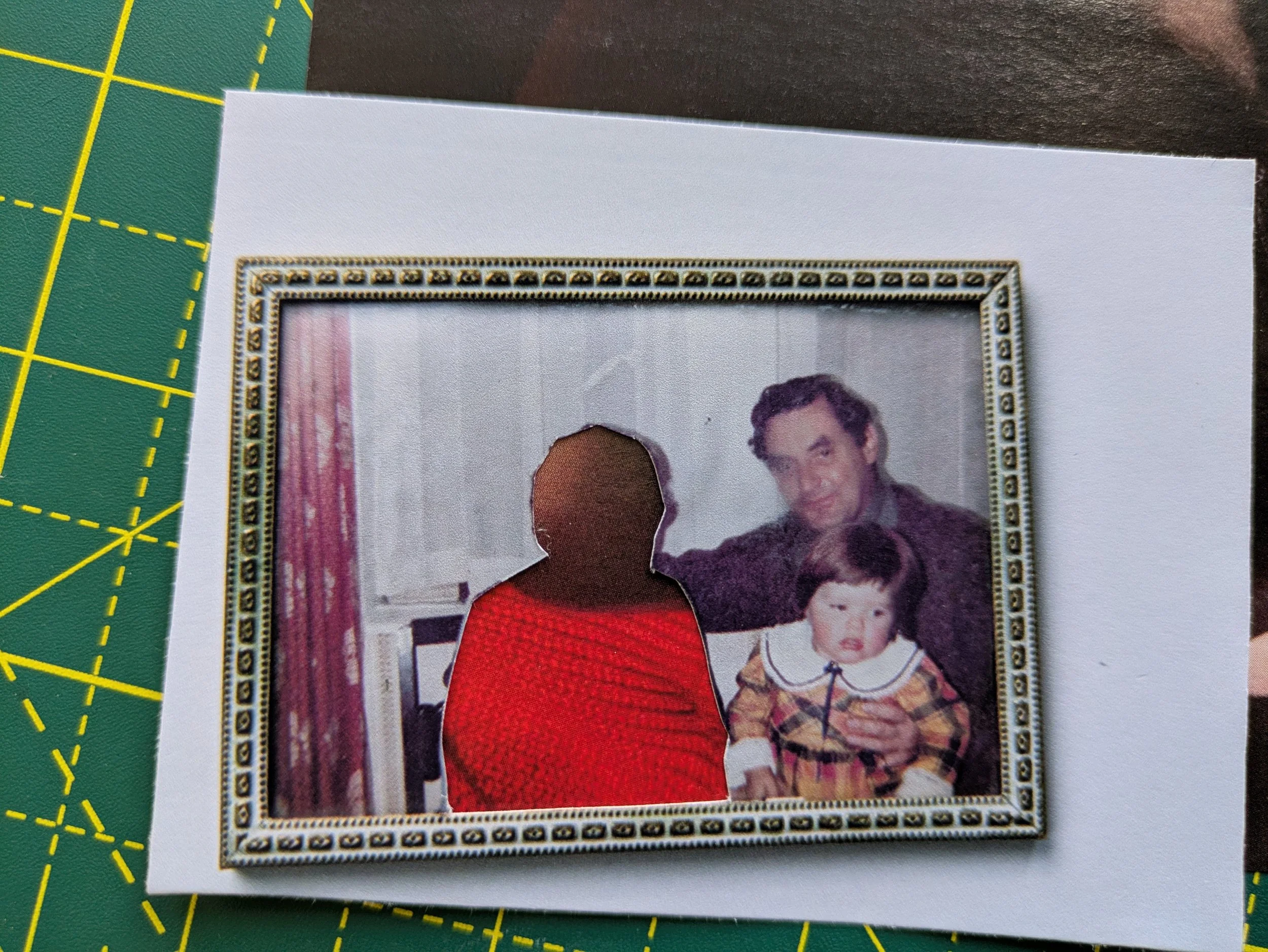

For me, this process of knitting threads from official documents together with oral narrative and images from our family albums was a catharsis, an active form of thinking about and re-configuring something which I find complicated and difficult and which holds a lot of historical baggage. Part of this involved me cutting into and disrupting photographs - removing people, drawing onto and generally messing with them in order to make sense of some of my feelings. What are the ethics of my doing this? My father’s generation are all dead but their stories and those of their forebears do not only belong to me - they are shared across different parts of my extended family.

My situated position within this nexus of kin requires some sensitivity but I also feel a pull towards reinstating these women within our family story. Perhaps I am now behaving as an arkon in my deciding what goes into this new narration and what stays out. I could argue that I have created a pint-sized family counter archive - something which aims to disrupt power dynamics and uncover/reconstitute a hidden narrative. Did I experience archive fever? Azoulay sees this malady as being about disrupting the status quo and pulling archives back into the present, so perhaps I did.

Azoulay, A. (2017). Archive in Political Concepts: A Critical Lexicon, Available at: https://www.politicalconcepts.org/archive-ariella-azoulay/#fn1

Derrida, J. (1995). Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression, Diacritics (25:2), Available: https://www.jstor.org/stable/465144?origin=crossref

Foucault, M. (1972). The Archaeology of knowledge, Pantheon Books, New York.

Stoler, A. (2002) Colonial archives and the arts of governance, Archival Science. Available http://link.springer.com/10.1007/BF02435632